I recently read Poor Charlie's Almanack. It’s essentially a collection of speeches that Charlie Munger has made over the years, touching on aspects of life, business, investing, sociology, and much more. Whenever I read a biography, I think it’s important to understand who the person is and how they developed into who they became. If you don’t know who Charlie Munger is, don’t sweat it—I’ll give you a brief overview.

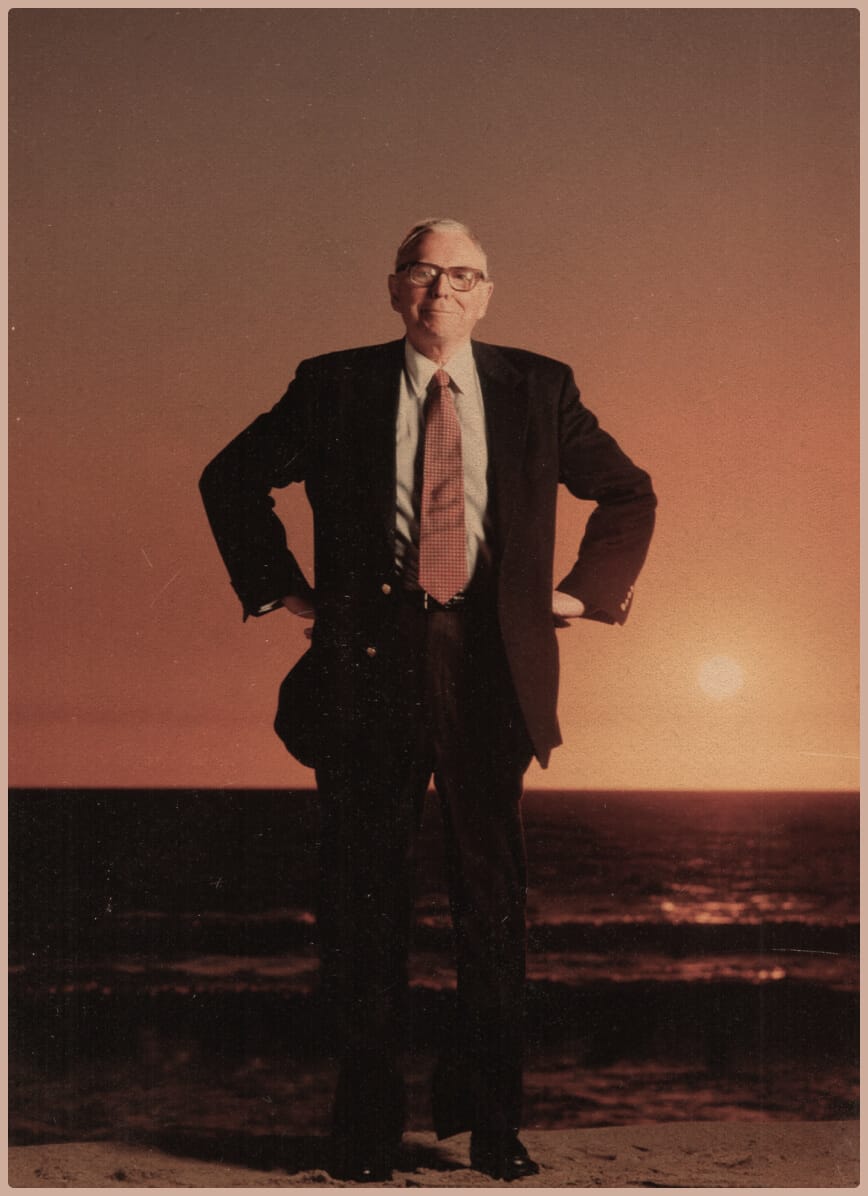

When you think of Berkshire Hathaway, the first name that likely comes to mind is Warren Buffett. But behind Buffett is someone who prefers to stay hidden and rarely gets the recognition he deserves: Charlie Munger.

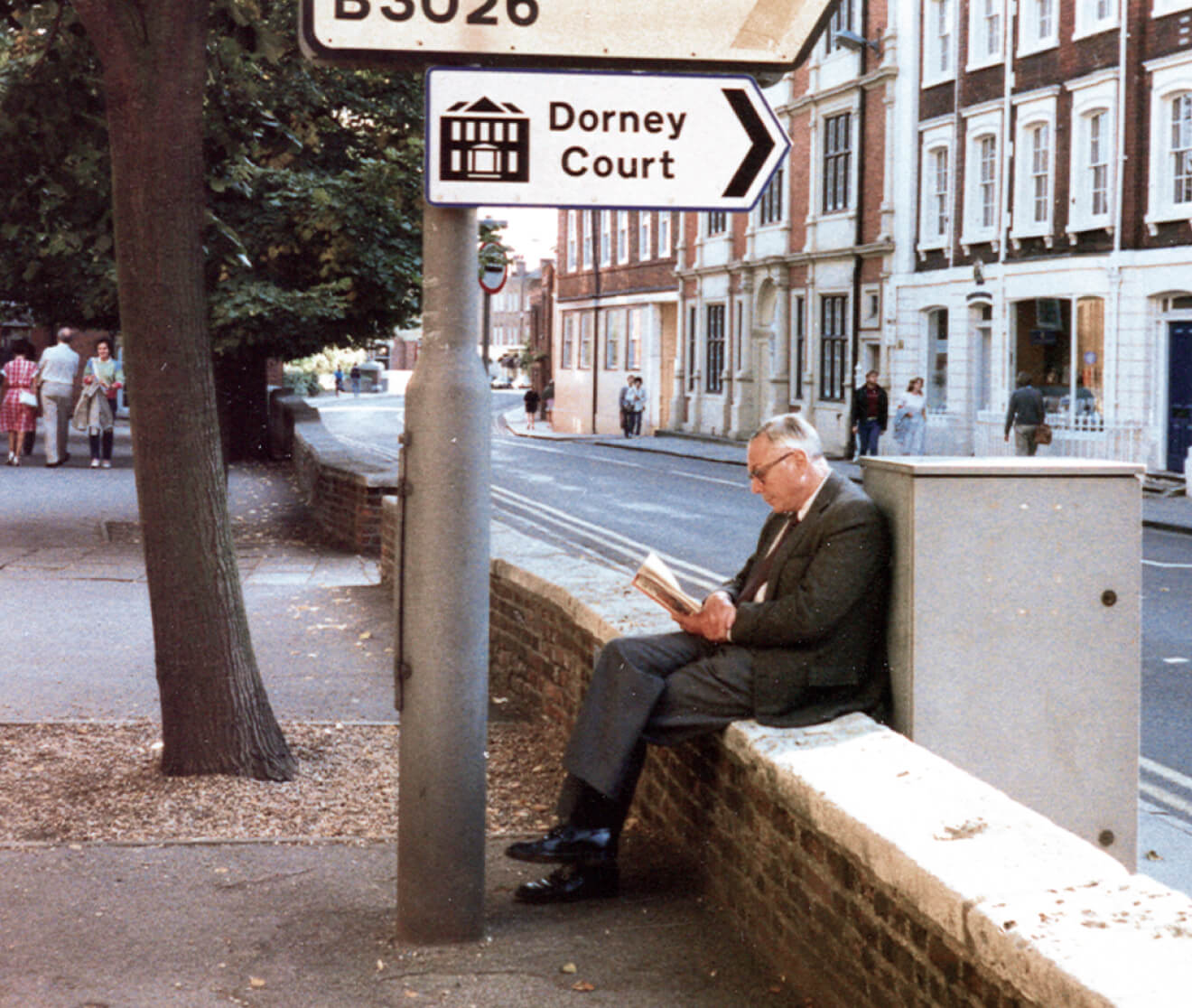

Charlie was born in Omaha, Nebraska. As a child, his teachers remembered him as a smart, curious kid who loved to challenge both his peers and teachers. He read voraciously and constantly sought to learn new ideas. One of the most influential figures in Charlie’s life was Benjamin Franklin. After reading Franklin’s autobiography, Charlie developed a deep admiration for him that lasted throughout his life.

Before attending college, Charlie enlisted in the Army, where he eventually became a second lieutenant. His grandfather, a judge, was another influential figure in his life, inspiring Charlie to pursue a career in law. He attended Harvard Law School and later joined a law firm in California.

He then married and had three children, but the marriage ended in divorce. Tragically, one of his children passed away from leukemia, a profoundly painful chapter in his life. But sometimes life is like a dark tunnel—you can’t always see the light at the end, but if you keep moving, you’ll eventually reach a better place. That’s what happened to Charlie.

He later met Nancy Borthwick, who had two young boys at the time, while Charlie had two daughters of similar ages. The two married and went on to have four more children together—three boys and one girl—bringing the total to eight. (Yes, eight! I was just as shocked when I read that.)

With his growing responsibilities, Charlie worked hard in his law practice. He sought to bring in clients and eventually became the firm’s leading money maker. However, Charlie always remembered a key lesson from Poor Charlie's Almanack: focus on the task at hand and control spending.

Eventually, he began exploring other ways to build wealth. Charlie started investing in stocks, ventured into property development, and even founded his law firm, Munger, Tolles & Hills. But over time, he realized he wanted to leave law and focus entirely on investing.

After his father passed away, Charlie returned to Omaha to handle the estate. While there, his childhood friends threw him a welcome home party. It was at that party that Charlie met Warren Buffett for the first time. They had heard of each other but never crossed paths. They ended up talking about a wide range of topics, from history to business, discovering they shared similar values and ideas. That conversation was the beginning of a partnership that would last for over 20 years.

Now that you’ve gotten an overview of Charlie’s life, I want to dive into his approach to thinking.

“Design a latticework of Mental models”

One of the first topics I want to discuss is Charlie’s idea of hanging your experiences on a "latticework of mental models." But what does that even mean? Imagine your brain as the top shape in a diagram, with various fields of knowledge—like psychology, biology, or history—represented by the shapes below. Each field you’ve studied or explored in life becomes part of this interconnected framework.

Charlie’s point is simple yet profound: to make better decisions, you need to draw on knowledge from multiple disciplines. This creates a mental framework—or "latticework"—that allows you to connect ideas and approach problems in more creative and effective ways.

Let’s break this down with an example. Say you work as a customer service representative at a company. Over time, you decide to learn more about psychology by watching videos and reading books because you want to become the best in your field. Normally, when interacting with clients, you might rush to explain what products or services they need. But after applying what you’ve learned from psychology, you take a different approach.

Instead of jumping straight into solutions, you start with a casual conversation. You let the client explain their concerns and issues, listening carefully. Based on what they share, you use your psychological insights to offer advice on the best product for their situation.

In this case, learning psychology not only added to your knowledge base but also fundamentally changed how you approach decision-making and interactions. That’s the power of building a mental latticework: it helps you see connections, approach problems differently, and make better decisions by pulling from a broad spectrum of ideas.

‘’To the man with a hammer, every problem tends to look pretty much like a nail’’

Many people fall victim to what Charlie Munger calls the "Man with a Hammer" effect: when you approach every problem or situation with the same tool or method, simply because it’s what you’re most familiar with. This approach is not only limiting but also fragile, as it fails to account for the complexity of new or unfamiliar challenges. Most of life’s toughest problems don’t fit neatly into the solutions we’ve relied on before.

Relying on a single perspective can put you at a disadvantage compared to others who draw on a variety of approaches and mental models from different disciplines. That’s why it’s so important to learn about diverse fields throughout your life—psychology, biology, history, and beyond. These disciplines are incredibly broad, offering endless areas to explore and deepen your understanding.

When studying these subjects, Charlie emphasizes focusing on their fundamental principles. These foundational ideas carry more weight than the smaller, more specialized ones. By mastering these fundamentals, you can combine knowledge from various fields to make better, more informed decisions.

“Always have a checklist”

Before airplane pilots take off, they go through a checklist to ensure everything is in order. So why don’t we apply the same approach in our minds before making decisions? This is a strategy Charlie Munger uses when evaluating investment opportunities: having a checklist helps avoid costly mistakes.

How do you develop your checklist? It starts with experience. In any field you work in, as you gain experience, you begin to develop a sense of what works and what doesn’t. Over time, you subconsciously create a mental checklist based on past successes and failures.

For example, let’s say you’ve invested in property before. On one occasion, a deal went wrong because you didn’t hire a property inspector. Later, you discovered that termites were eating through the foundation of the house, which caused significant issues. However, in another investment, you made a successful purchase by thoroughly understanding the property’s value, securing a loan, fixing it up, and renting it to tenants.

From these experiences, you naturally begin to form a mental checklist. First, you learn that hiring a property inspector is non-negotiable. Second, you understand the importance of evaluating a property’s value. Third, you recognize the steps needed to turn the property into a profitable investment.

This is just one example of building a checklist, but the concept applies broadly. Whether in investing, business, or personal decisions, creating a mental or physical checklist can help you avoid repeating mistakes and improve your decision-making process.

"Invert always Invert"

Charlie Munger often emphasizes the power of inversion, famously saying, "Invert, always invert." I’ve found this approach to be incredibly useful when tackling problems. Instead of asking, “What makes something good?” inversion flips the question to, “What makes something bad?” This shift in perspective helps narrow down the critical elements of a solution.

Let’s imagine you’re building a car. If you start by asking, “What makes a good car?” you might compile an overwhelming list of features—everything from the engine to the interior design to the type of tires. The list could become so extensive that it’s hard to focus on what matters.

Now, let’s invert the question: “What makes a bad car?” This simple shift forces you to prioritize the most important elements. For instance, you’d likely identify that a bad car lacks a reliable engine, functioning wheels, and proper headlights for visibility at night. By focusing on what to avoid, you can pinpoint the essential components a good car must have without getting lost in less critical details.

I’ll admit I’m not a car enthusiast, so this example might not be perfect, but I hope it helps illustrate the concept. Inversion is a powerful mental model that simplifies complex problems by shifting your perspective. Instead of being overwhelmed by possibilities, you focus on eliminating pitfalls, which often leads to clearer, better decisions.

“Practice that mimics an aircraft simulator prevents skills being lost in disuse”

Now that you’ve learned a bit about how Charlie Munger thinks, I encourage you to try at least one of these approaches in your own life. You’ll be amazed at how much better your thinking becomes when you incorporate even one of these strategies. And if you manage to apply all of them, you’ll find yourself ahead of most people in terms of decision-making and problem-solving.

Like anything worthwhile in life, mastering these approaches requires practice. Over time, as you use them more, they’ll become second nature. For the multidisciplinary models, start by drawing a simple diagram on a sheet of paper. Write down a subject you’ve studied and list the most important ideas you’ve learned. When faced with a question or problem, practice inversion—flip the perspective and see where it takes you.

As for the “man with a hammer” effect and the checklist, these tools tend to develop with time and experience. Keep them in mind as you pick up new skills and gain more knowledge. Gradually, they’ll become integral to how you approach challenges and make decisions.

I hope this article gave you some new insights into Charlie Munger’s way of thinking. If you’d like me to explore more about Charlie’s approaches to thinking, business, or life advice, let me know! I didn’t cover everything from Poor Charlie’s Almanack, but I’m considering turning this into a series where I dive deeper into his teachings.